I have launched a podcast! You can also listen to this post on Spotify

Find me on LinkedIn @tejasinamdar, Twitter @tejasinamdar_ and tejasinamdar.com

Warning: This series of posts is long, like a CVS receipt.

There is tons of stuff out there on the interweb about Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBM). A lot is happening in the policy space right now, and it’s worth capturing the state of affairs. Part 1 of this series covers the market players and some industry jargon. Part 2 of the series covers the history of how PBMs became powerful and their interactions with other market players. Part 3 of the series covers the ever-evolving business model, the systemic problems, and emerging developments on the regulatory and strategy front.

Oligopoly or Oligopsony - a perfectly imperfect market

Slippery slope

In 1987, President Reagan signed a bill that allowed safe harbors to the Medicare Anti-Kickback Statute (AKS). The AKS provides criminal penalties for knowingly and willfully offering, paying, soliciting, or receiving remuneration to induce business reimbursed under government health care programs. The offense is classified as a felony and is punishable by fines up to $25,000 and imprisonment of up to 5 years.

With the safe harbor, PBMs could negotiate discounts with Manufacturers in the form of rebates. The rebate would flow from the drug maker to the PBM to the Health Insurer and the Plan Sponsor after the initial point of sale transaction when the patient bought the drug from the Pharmacy.

In 1996, pharmacies settled a lawsuit against the Wholesalers and Manufacturers that refused to offer pharmacies the same rebates they were offering to purchasers like hospitals and health insurance plans. The settlement expanded the beneficiaries of the rebates to pharmacies that were able to demonstrate large market shares. In 1999, the safe harbor rule was revised to exempt all rebates from AKS after the initial point of sale of a drug.

King Kong vs. Godzilla

Leverage matters in any negotiation. PBMs consolidated over the last three decades and drove the growth of an opaque and self-dealing business model. If the success of a PBM was linked to its ability to negotiate price concessions, trust from Plan Sponsors, Health Insurers, Providers, and Pharmacies would have been the PBMs most vital asset. Instead of policing the system, PBMs recognized the leverage they held and maximized the opacity of drug pricing to its own benefit.

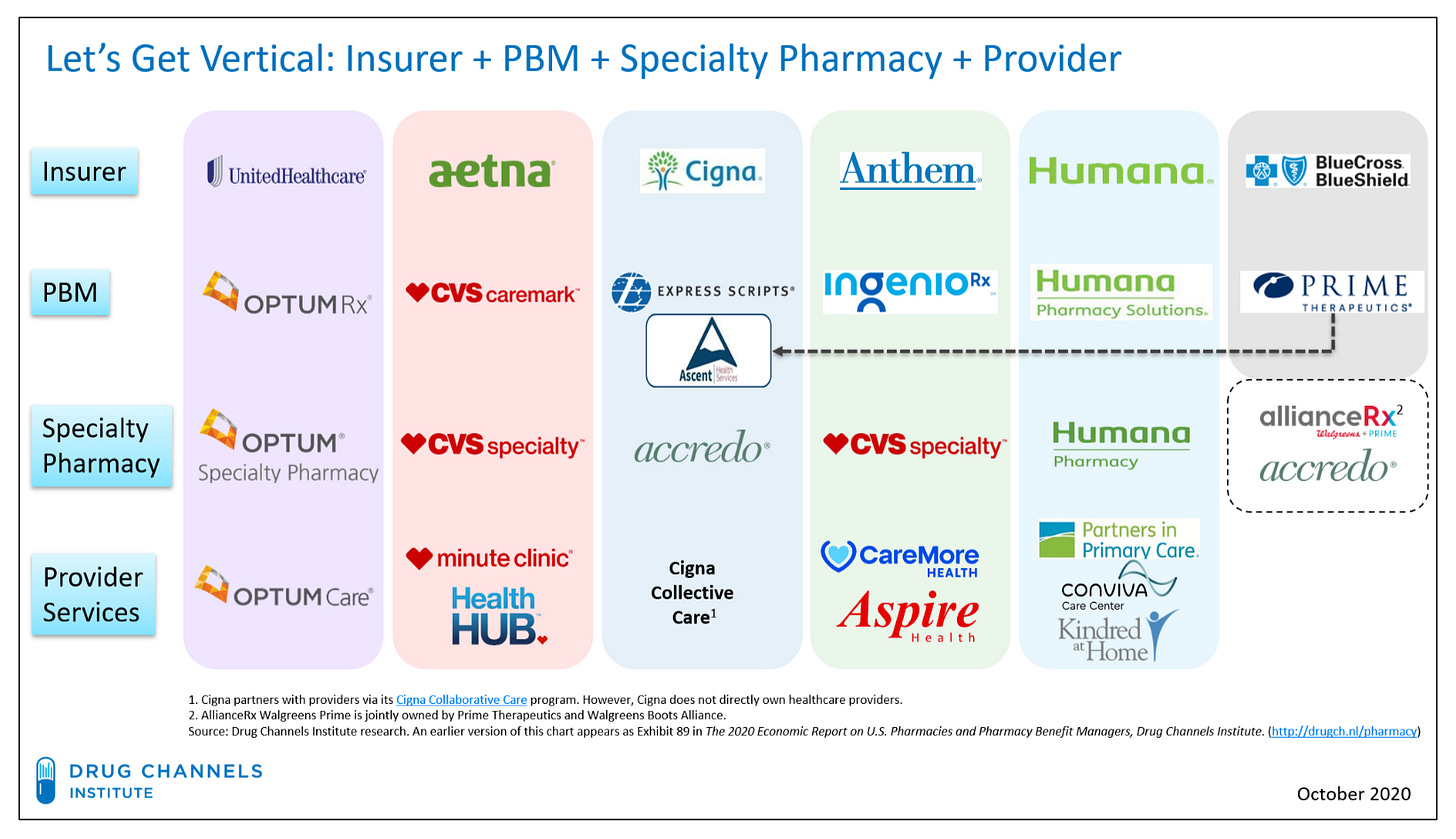

The AKS exemption paved the way for an expanding universe of PBM services. Over time, PBMs realized they could have even more leverage if they horizontally integrated. In 2011, Medco merged with Express Scripts. In 2015, Prime merged with Express Scripts. In 2013, SXC merged with Catalyst to form Catamaran. In 2015, Catamaran was acquired by OptumRx. Consolidation led to more consolidation. Health Insurers realized that PBMs were minting money, and it was worth absorbing them rather than paying them. PBMs started offering their own mail-order pharmacy services, effectively competing against the pharmacies they were supposed to pay. In some cases, brick-and-mortar pharmacies were also merged together. In 2007, CVS acquired Caremark. In 2018, CVS acquired Aetna. The same year, Cigna acquired Express Scripts. Horizontal and Vertical integrations across the pharmacy value chain created 800-pound gorillas that operated as oligopolies (few dominant sellers of pharmacy benefits) and oligopsonies (few dominant buyers of pharmacy benefits)

Let’s look at some fundamental interactions -

PBMs and Manufacturers

The belief that PBMs could enhance efficiency and lower drug spending through leverage and consolidation is fundamentally misguided. This is probably the only economic model in which a Manufacturer gains market share by raising prices!

For Manufacturers, a drug’s position on a PBM’s formulary is a make-or-break deal. Patients will have difficulty accessing drugs lower on the formulary because of a higher copay. Recognizing this issue, some Manufacturers will offer copay assistance to Patients through coupons. The other strategy is to provide discounts to PBMs in the form of rebates in exchange for higher formulary placement. The rebates are offered as a percentage of the list price. Higher the price, the higher the rebate. These rebates flow from the Manufacturer to the PBM and then to the Health Insurer and the Plan Sponsor. PBMs take a cut of the rebate, so the larger a rebate is, the more the PBM can profit. In the absence of safe harbor from the Medicare Anti-Kickback-Statute (AKS), offering and accepting rebates is a felony.

Rather than compete on the price or efficacy of the drug, Manufacturers compete by offering higher rebates to the PBM. In fact, PBMs prefer Manufacturers give price concessions in the form of rebates that are partially retained by the PBM rather than price cuts. Manufacturers have responded by raising list prices and rebates to compete for higher placement on the PBM’s formulary. The consolidation in the PBM market effectively shuts out anyone who would want to end-run the system and compete on prices. PBMs will also extract rebates from Manufacturers who rock the boat by threatening to exclude drugs from the formulary. The BioSimilars market (generics for Biologic drugs) that could lower drug costs is being stifled and held captive to these types of rebate traps. However, there are emerging signs of Direct to Consumer models or cost-plus models that could disrupt the status quo by cutting out the gatekeepers. That’s probably only until the current actors figure out how to make money in a new market.

PBMs and Pharmacies

Today, there are three superpowers: The CVS-Aetna empire, the Cigna-Express Scripts empire, and the United Health-OptumRx empire. They manage almost 80% of all US prescription claims. Migrating from one empire to another is not easy.

The three superpowers responsible for lowering drug costs also have their own Pharmacy. They own mail-order pharmacies, they own specialty pharmacies, and some even own brick-and-mortar pharmacies. The combined entity profits as the volume and price of prescriptions dispensed at its own pharmacies increases. The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) has turned a blind eye to conflict of interest for a long time. However, there are promising signs of change on the regulatory front.

Independent pharmacies have little leverage. DIR Fees and Clawbacks are essentially surprise bills for pharmacies and can be charged months after the patient buys the drug, creating a cash flow problem. DIR fees can amount to hundreds of thousands of dollars and have increased by more than 90,000 % from 2010 to 2019. In some regions, a single PBM can account for 85% of the market. Being out of network with just one PBM could make business unviable. Under-reimbursement, surprise audits, network access, and other fees have brought many pharmacies to the brink of bankruptcy. The local pharmacist is an important front-line healthcare provider trusted by Patients. Their disappearance will not bode well for access to care.

PBMs and Plan Sponsors

The lack of transparency in healthcare isn’t new. There have been great strides on the medical front with the No Surprises Act, the Hospital Price Transparency Rule, and The Transparency in Coverage Rule. The last rule had expansive requirements for drug price disclosure but got pulled out and indefinitely delayed.

Plan Sponsors such as self-insured employers know very little about the actual cost of the drugs or the profits made by PBMs. Smaller employers or Health Insurers have even less information owing to the lack of leverage in forcing disclosure.

Net prices for brand-name drugs have been growing more than 7 percent per year, while List prices grew by 10 percent per year. Plan Sponsors and Health Insurers likely notice similar price hikes, given that they rely on PBMs to negotiate their net price. PBMs and Plan Sponsor contracts allow PBMs to keep a share of the rebates from Manufacturers while passing through most of the rebate. However, many plans don’t know about another industry player - the Rebate Aggregator or Group Purchasing Organization (GPO) (covered in detail in Part 3) that is owned by the PBM. This new player takes the first cut of the rebate before passing it on.

Plan Sponsors do not know the Maximum Allowable Cost (MAC) negotiated by the PBM with the Pharmacy. As a result, Plan Sponsors have no idea how much they are being overcharged. This type of “spread pricing” is widespread in commercial plans. It is especially common in the case of generics, where there can be a wide gap between a percentage of the List Price paid by the Plan Sponsor and the MAC.

PBMs and Health Insurers: The three largest PBMs have merged with a Health Insurer. So the distinction between PBMs and Health Insurers has become blurry. PBMs have gone from entities that aggregate demand and lower drug costs for health sponsors those that also aggregate supply by becoming pharmacies themselves rather than just the middleman. Health Insurers recognized this lack of incentive on the part of PBMs to control drug costs and have merged with them. Not to restructure incentives but to partake in the profits.

Take 2 mins to listen to this stunning testimony by Pharma execs.

When drug prices are driven up, they are driven up because PBMs profit off of spread pricing and higher rebates from Manufacturers. PBMs have an incentive to keep prices high. The rising prices affect everyone in the healthcare ecosystem. In fact, everyone except for Plan Sponsors and Patients profit from higher prices. Patients are at the bottom of the totem pole. Their out-of-pocket costs are dictated by inflated List prices rather than net prices after accounting for all the rebates.

Let’s take a break here! Pharmacy is way, way, way more complex and we obviously haven’t covered many important aspects of this complex industry. Do you work in the pharma space? Do you know this stuff really well? Reach out or comment below and share where I got things right and where I got them wrong. Always open to feedback!

Thanks for reading hick-picks! If you enjoyed reading, please like, comment, share and subscribe. Find me on LinkedIn, Twitter, tejasinamdar.com

PBM

Drug company executives are honest in replying in the hearing. But they will do nothing to reduce prices. They want to keep shareholders happy. All the money received by shareholders will come back to pharmaceutical companies when they will be required to pay as patients. It all goes around.